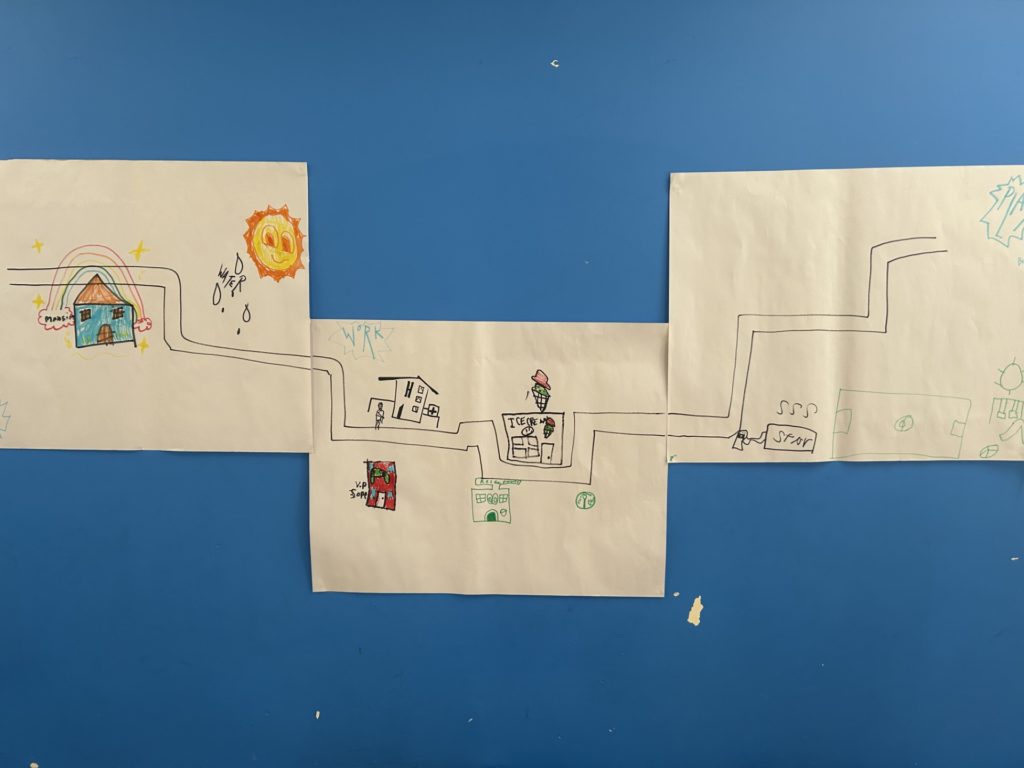

On a Friday evening earlier this spring at St Edward’s School, the stage was set – not for an ordinary performance but for something built from the ground up by the imaginations of Oxford’s young people. The Let’s Build a Town! concert, led by Music at Oxford (MaO), alongside students from Oxford’s St Francis C of E Primary School and Oxford Spires Academy, was the culmination of a series of creative workshops with the schools, in which children designed their own town – one without adults, shaped entirely by their ideas of an ideal community.

Under the guidance of professional musicians, educators and theatre-makers, the children transformed their ideas into music, theatre and movement. In the spirit of composer Paul Hindemith’s 1930 original, which inspired the collaborative project, young people from Oxford made his nearly century-old work feel entirely fresh and current as they performed co-created music and theatre which spoke to contemporary issues of community-building and identity.

After the performance, participants and members of the artistic team took part in a talk with audience members, sharing insights into the project and its impact on the young participants’ confidence and creative skills.

For Giles Masters, Fellow at Magdalen College and curator of the project, the experience was as inspiring as it was moving. Read what he had to say:

“To witness our town come to life through performance was joyful and moving. The children used their creativity, teamwork and all sorts of different skills – singing, dancing, speaking, playing, building – to create something that was so much more than the sum of its parts. I loved seeing how they rose to the occasion of the performance and how proud they and their families were of what they had achieved.

If I had to choose highlights (which is hard – there were so many!), I would pick out two things. First, the announcements between scenes, when children took turns to come up to the microphone in the middle of the stage to share some of their ideas about what their ideal town might be like (we need enormous 6-decker buses, obviously). These were by turns funny, charming and genuinely thought-provoking. I was really impressed by how brave all the young people were about speaking to such a big audience!

Second, as the music historian on the project, I really enjoyed seeing how much the children took to singing Hindemith’s music and making it their own. Although Hindemith’s original piece is nearly 100 years old, through their energy and commitment, the young people from St Francis made it feel totally fresh and of today.

Many thanks and congratulations to all the participants, the schools, our creative team and our partner organisations for joining us on this project – you achieved something really special. Now, it’s time for everyone to lay down their buckets and shovels and enjoy a well-earned break.”

‘Let’s Build a Town!’ captured the energy and creativity of the young performers, and offered a thought-provoking reflection on the ways we build and shape communities today.

For Felicity Newby-Smith, Educational lead from Music at Oxford, the project was more than just a performance – it was a journey of personal transformation for many of the young participants, read as she reflects on the event:

“The joy surrounding the performance on the night was completely infectious; there was laughter, cheering and applause, and I loved looking around the audience to see huge smiles on so many adults’ faces! For grown-up members of the audience it was a reminder of how to be a child; how to play, how to create something from almost nothing and ultimately how to have fun!

The children from St. Francis Primary School who performed on the night blew me away with their commitment, confidence and energy. This was visible (and audible!) while watching them perform as a group, and the team work that involved, but what was really special to me was the added awareness of the journeys individual children had taken during our project Let’s Build a Town!. When we first arrived in January, there were a few children who were so lacking in confidence that they struggled to even engage in simple classroom discussions or warm-up games. Fast-forward to the final performance and I had to pinch myself as I watched those same children performing with such dedication and confidence, in some cases having chosen solo roles for themselves, all in front of 300 members of the audience!

I’ve always known that the value of making music is unparalleled, especially for children, but what I wasn’t expecting was the realisation that by engaging with the performing arts, even for a relatively short period of time, those children had gained transformational skills that would set them up for the rest of their lives.”

By the end of the evening, it was clear that Let’s Build a Town! had created something far greater than just a performance. It had built confidence, creativity, and a sense of shared community among the children, teachers, and artists involved.

Let’s Built a Town was produced by Music at Oxford in collaboration with The University of Oxford’s Cultural Programme, and with the support of the Faculty of Music, Magdalen College, RETUNE Festival and the Marchus Trust.

Featured image: Simon Vail Photography

Ahead of A Grand Celebration of Le Concert Spirituel at the Sheldonian Theatre on 13 June, we sat down with conductor Edward Higginbottom to explore the origins of one of Europe’s earliest public concert series, and its legacy. From the distinctive sound of period instruments to the interpretive choices behind historically informed performances, Edward Higginbottom’s reflections on Le Concert Spirituel offer a fascinating glimpse into a musical world that still echoes in our own.

Could you tell us about Le Concert Spirituel, and how it began?

Edward Higginbottom: Le Concert Spirituel is a concert organisation in Paris, begun in 1725, by Anne Danican Philidor. And, you might ask, why ‘spirituel’? Because Philidor always had a grand motet Psalm setting in the programme. And why was that? These concerts always took place on a Christian feast day, so Christmas, Easter, Ascension. There were quite a number of them, in the year maybe 20, or 25.

And why on those occasions? Because the opera was shut. If you were a music lover in Paris in those days, there was nowhere else to go. If the opera was shut, what could you do about your music consumption? Philidor had the idea of offering these concerts, which would recognise the Christian nature of the day, but also offer a wide range of other sorts of music. This was an organisation that put on concerts, over 1000 of them, throughout more or less the whole of the 18th century, and was a crucial feature of public music making in Paris, and indeed in Europe, of the day.

What role did it play in shaping the idea of a ‘public concert’?

EH: We’re very used to public concerts in our own day. We see them advertised, we buy a ticket, and we go. In the 18th century, early on, there was no such thing, until Philidor came along and said, “we’ve got this concert, this programme of music, you can come if you pay adequately, and hear our best performers”, so that was quite a novelty.

It had been going on [before 1725] in aristocratic homes, in the homes of the wealthy. Privately, it had been going on at court. But as a public subscription event, it wasn’t really a part of the social life, the musical life in Paris, until this point, so it’s really significant. It marks a moment when the public concert became a thing, and you could book and go, and enjoy, or hiss or boo, whichever you liked! It was about the public consumption of music for the first time on a significant level.

And what sort of music would a listener have heard at a Concert Spirituel performance? Was there a standard programme?

EH: The type of music you would hear at the Concert Spirituel comprised, always, a grand motet, a large-scale cantata setting of about 20-25 minutes, which would be a psalm setting. That was the significant nod to the Christian feast day – that was always part and parcel of the event, because quite often, you’d have been to church in the morning for mass and would go to the concert in the afternoon. So, there would be a big choral item, orchestral and choral music, and then there’d be some instrumental music.

At the very first concert there was [Arcangelo] Corelli, and his Christmas concerto was played. And that sort of music, Italian-based concerto music, became a mainstay of the programme planning. A lot of concerto composers are represented in the programmes. The symphony also crept in. There weren’t really any symphonies in 1725, which we’d recognise these days as symphonies. But bit by bit, this genre, a very public genre, took hold and found a place in the Concert Spirituel, so very important instrumental genres were represented in the programme.

And then you might have rather small-scale things. One of the things we’re performing on the 13th of June is a very small-scale cantata by [Louis-Nicolas] Clérambault. That’s unusual in respect of it reducing to just five performers, from a big orchestra and chorus. That doesn’t often happen in modern concerts, because you tend to stay with the group that’s installed on the stage. But they had a lot of variety, solo items, larger items, and then these full-scale symphonic items. So it’s a real melee of music, a lot of different stuff, and increasingly, putting an accent on the instrumental.

In what other ways would the experience of attending a Concert Spirituel performance differ from we’re familiar with now?

EH: I think the public was much pickier than we expect concert audiences to be today! For instance, when Mozart composed his symphony for the Concert Spirituel, which we know now as the Paris symphony, which we are going to play [on 13 June], in 1778, at the first performance, the slow movement was not much appreciated. In fact, it was criticised in the press as being overly complex. The second performance was a chance that Mozart then had to do something about that. So, he composed another slow movement, which was duly played on the second performance, and applauded more warmly by the press and public. The response from the public was in a manner that was more unbuttoned, and [the public] would say what it thought. When we do our concert on the 13th of June, we’re going to play both of these slow movements, and we’re going to ask the audience to indicate which they preferred. We’ll have a couple of urns where you’ll be able to drop a token to let us know which movement you preferred.

Another difference was the diversity of repertory. There’d be small scale, there’d be choral, there’d be instrumental, there’d be people who were valued for their prowess as soloists – concerto soloists and vocal soloists. That rich mixture of everything you could possibly hear musically, chamber music up to the grand scale, would be present at these events.

Could we talk about the instruments themselves? What sets ‘period performance’ apart, and how does it shape the way we experience 18th-century music today?

EH: Quite often people ask what it is about period ensembles, or period performance, that’s different. The primary difference is the instruments used. These are instruments which are either 18th century instruments, or copies of 18th century instruments, and they’re not the same [as instruments today]. The violins have less of an angle on the fingerboard, they don’t have a chinrest, they have gut strings, the bows are not shaped in the same way. The sound you get from them is definitely different.

The woodwind instruments, the flutes and the oboes, are differently constructed and have fewer keys and a different timbre. The brass instruments are natural and have no pistons. It’s quite a different sound world. It requires proficiency on those instruments. Then there is a way of performing the music, which bit by bit you can forget. Of course, in their day, you wouldn’t think at all that what you’re doing could be part of the currency of the time. But if you perform 18th century music now, you have to look carefully at the evidence concerning how it was performed. There’s a lot of evidence, including treatises on performance, on various ways of playing your instrument, and various ways of construing the notation.

The notation tended to be quite economical. You’d certainly have the notes, their values and their pitches, but dynamics – a few, not many. Crescendo, diminuendo marks – not many of those either. Phrasing – not at all, really, some bow marks. There’s a lot you have to see underneath that notation, or behind it, to get the best out of this music, so that is what we are doing when we play period instruments and perform in a period style.

A Grand Celebration of Le Concert Spirituel takes place on 13 June at the Sheldonian Theatre, Oxford. Join us for an evocative evening of music that reimagines one of Europe’s most influential early concert series.

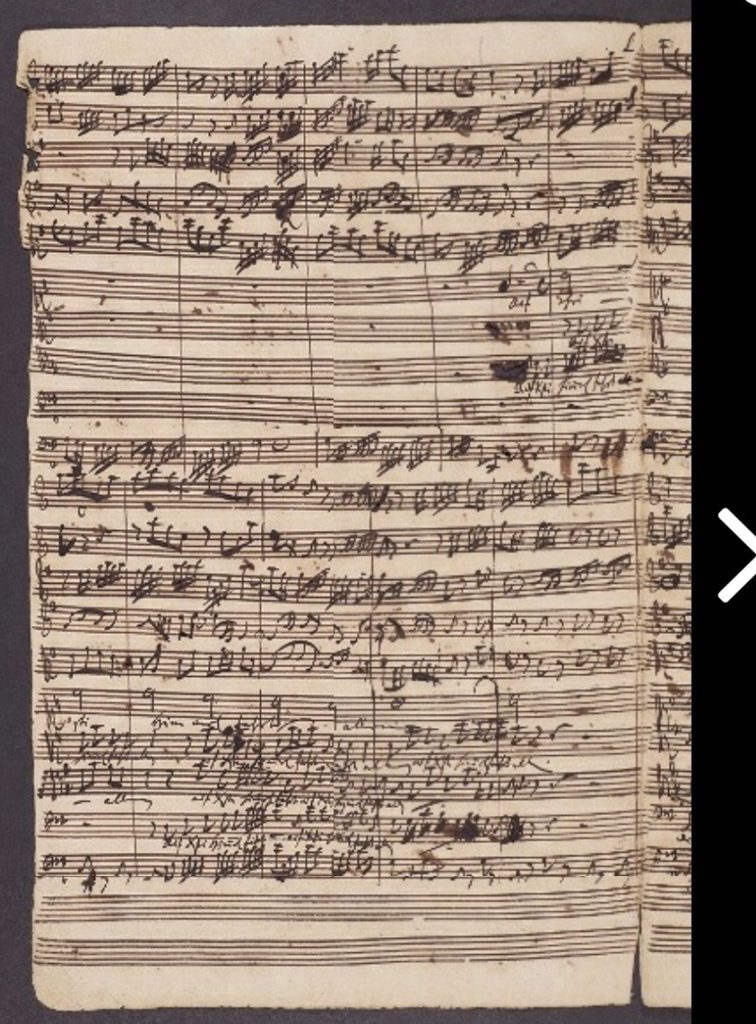

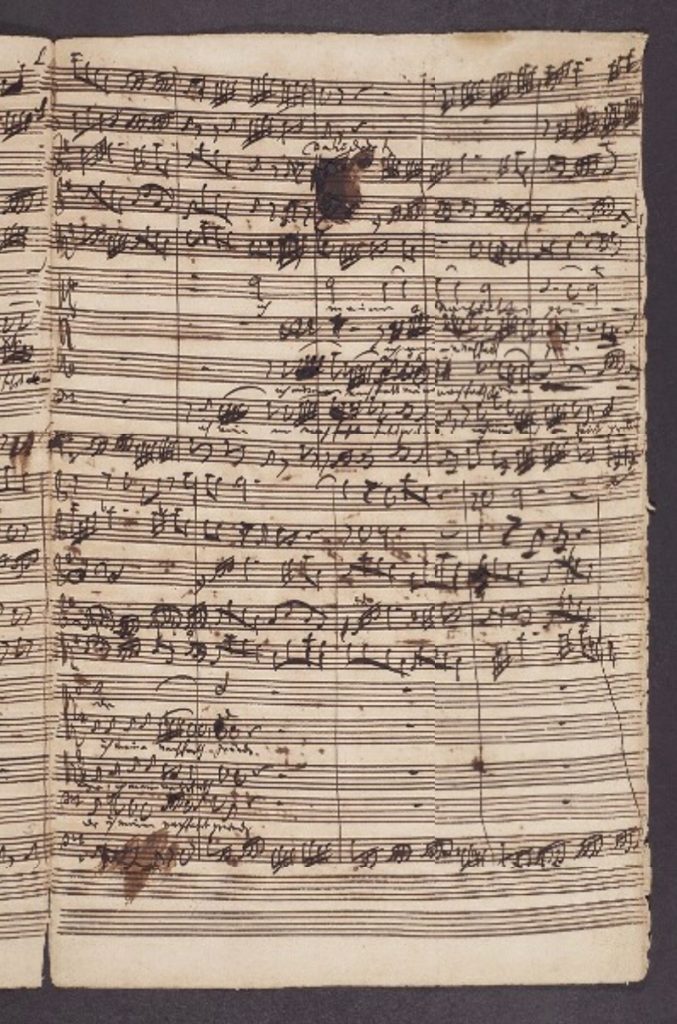

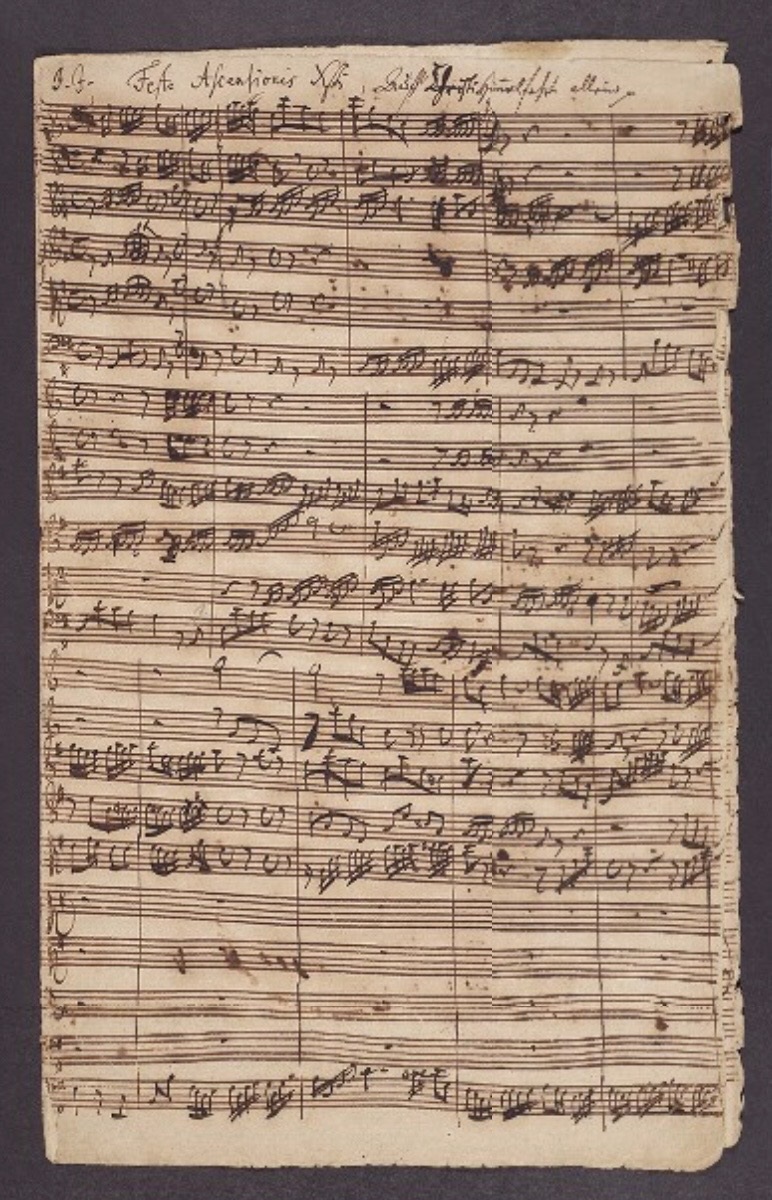

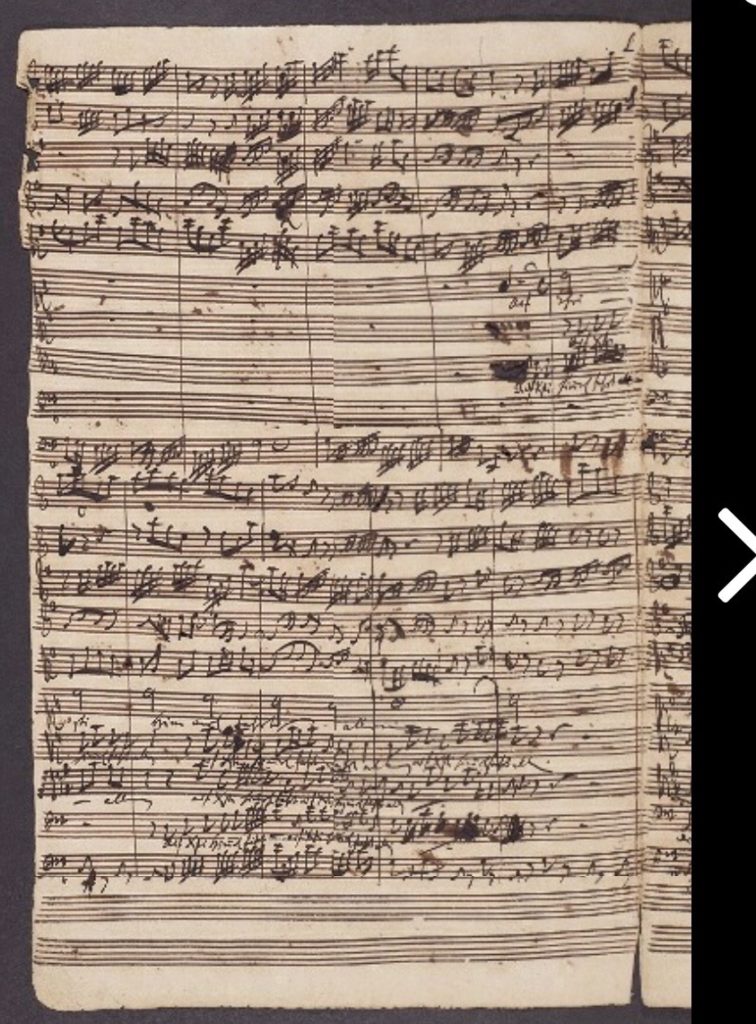

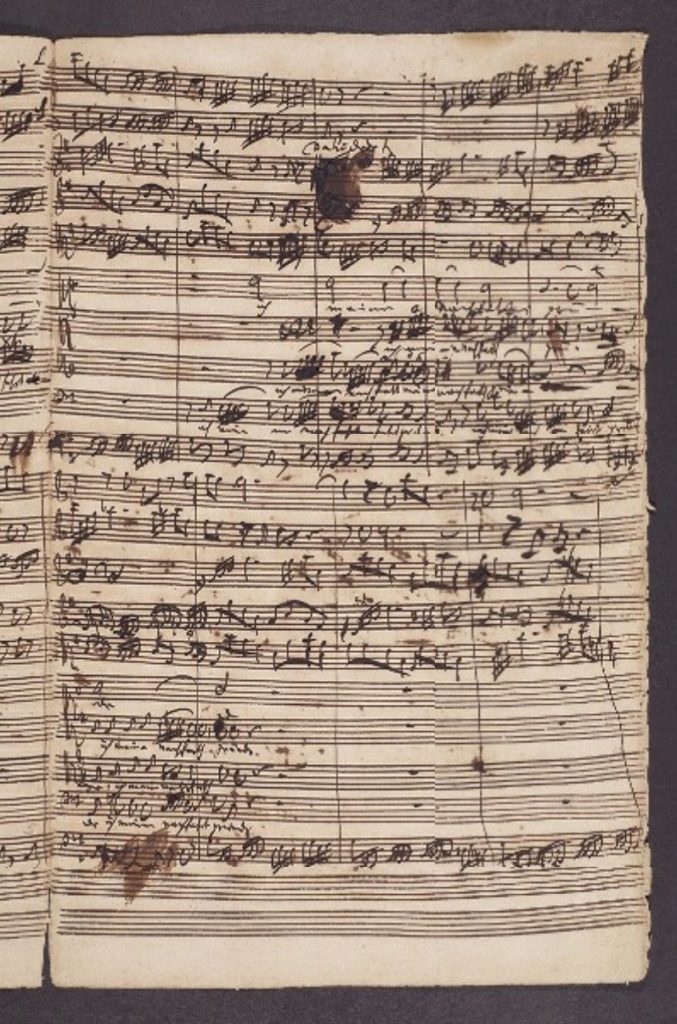

As preparations are underway for a special concert tomorrow night (Wednesday 7 May) celebrating the music of Johann Sebastian Bach, we take a moment to reflect on the remarkable journey of the manuscript that inspired Bach 1725. Newly acquired by the Bodleian Libraries in 2024, this treasured document, rich with historical significance, offers a rare glimpse into Bach’s creative process in the mid-1720s. In the article below, the Bodleian Libraries’ Alfred Brendel Curator of Music, Martin Holmes, explores the story behind the manuscript, tracing its path through the centuries to its new home in Oxford, and the steps taken to preserve it for future generations.

News that the Bodleian Libraries might acquire a Bach autograph first reached me in April 2023. Since only two other institutions in the country have Bach autograph manuscripts in their possession, the possibility of one coming to Oxford was immensely exciting. It was being offered in lieu of inheritance tax by the family of Sir Ralph and Lady Kohn and the application was being handled by Sotheby’s. I was immediately set to work on building a case for Oxford as the Government began the process of assessing the tax value of the manuscript and deciding to which institution it should be allocated. It was known that the Kohn family were keen for it to come to the Bodleian but that outcome was not a foregone conclusion. However, with the help of Dr Stephen Roe (formerly of Sotheby’s) and current Sotheby’s staff, the application was assembled and after a tense few months the final decision to allocate the manuscript to the Bodleian was made by the then Secretary of State and communicated to Bodley’s Librarian by Arts Council England. The manuscript was delivered to Oxford on 29 January 2024 and unpacked with much anticipation (and not a little trepidation) by Bodley’s Librarian and a small group of senior Special Collections staff.

Sir Ralph Kohn (1927–2016) had purchased the manuscript at a Sotheby’s sale in 1989, and it was considered to be the last major Bach manuscript in private hands. Sir Ralph was a distinguished biomedical scientist and pharmaceutical entrepreneur. He was also a keen musician and an accomplished amateur singer who, having been born in Leipzig, felt a natural affinity with J.S. Bach. A discerning collector, he built up a choice collection of musical manuscripts and first editions of works which meant a lot to him.

After Bach’s death in 1750, the manuscript scores of most of his works were inherited by his eldest son, Wilhelm Friedemann (1710–1784) who was living in Halle at the time. It is clear that W.F. Bach performed the work himself at some point, since some of his markings have been detected on the manuscript. He moved to Berlin in 1774 where he remained for the rest of his life and taught the harpsichord to Sarah Levy, Felix Mendelssohn’s great-aunt.

What happened to the manuscript next is not quite clear. W.F. Bach is known to have had financial troubles and sold off some of his father’s manuscripts. However, in 1827, it was acquired, along with manuscripts of a dozen more cantatas from W.F. Bach’s estate, by Carl Pistor (1778–1847), a civil servant with an obsession for precision optical instruments, which he manufactured in conjunction with one of Felix Mendelssohn’s uncles. He was also a passionate music lover and gave the young Felix the task of sorting his collection. Pistor’s daughter Betty sang with Mendelssohn in the Berlin Singakademie and she was the object of his teenage affections for a while until a rift developed between the two families. Betty Pistor eventually married Adolf A.F. Rudorff (1803–1873) and the manuscript remained in their possession until around 1854 when it was given to the conductor and composer Robert Radecke (1830–1911). From him, it passed to his grandson, Ewald Radecke (1907–1979) and it remained in the Radecke family until coming to auction at Sotheby’s in 1989.

The manuscript comprises sixteen pages in four unbound bifolia. In common with most of Bach’s manuscripts, it was written on paper with corrosive iron-gall ink which presents modern conservators with a considerable challenge if these documents are to survive for future generations to study and enjoy. A particular problem with music notation is that the forming of note heads causes high concentration of ink in small areas which often causes brown discoloration beside the ink and through the paper. In acute cases, the ink can literally burn through the paper, creating cracks and losses where notes should be and severely weakening the structure of the paper. Given the corrosive nature of the ink Bach used, it is difficult to arrest this process completely.

Over the years, Bach manuscripts have been subjected to a variety of treatments, from splitting each page in two and inserting an acid-free barrier between them, to washing the paper with alkaline solutions. The Bodleian’s approach in this case is to avoid interventive measures and provide effective mitigation solutions. The priority will be to ensure that the manuscript can be securely housed and handled without risk of further damage. The bifolia, protected in custom made archival folders and box, will be stored in controlled environmental conditions. Handling will be kept to an absolute minimum. No further treatment is planned at this stage.

As soon as it arrived in Oxford, the manuscript was photographed by the Bodleian’s studio and high-quality digital images are now freely available in Digital Bodleian. Scans can never be a complete substitute for an original manuscript but the images will enable scholars and others with an interest in Bach to study many aspects of the music and the process of its composition without having to handle the original. In due course, modern multi-spectral imaging techniques could be used to reveal more about aspects of the manuscript which are less obvious to the naked eye, such as different layers of annotations on the score.

The cantata was first edited for publication by A. Dörffel in 1878, for the Bach-Gesellschaft edition, and the manuscript was presumably borrowed for that purpose. Indeed, discrete markings can be found in the manuscript which were added at that time. In 1960, it was re-edited by Alfred Dürr for the Neue Bach-Ausgabe, taking account of a surviving set of performing parts in Berlin. It is therefore unlikely that renewed study of the Kohn manuscript will cause radical changes to be made to the accepted musical text of the work. However, the manuscript will enable successive generations of scholars and students to see how Bach committed his thoughts to paper and feel the presence of one of the greatest musical geniuses of all time.

Martin Holmes is the Alfred Brendel Curator of Music, Bodleian Libraries. He studied Music at Worcester College, Oxford and first joined the Bodleian’s Music Section nearly forty years ago. After several cataloguing projects in Music and Rare Books, including the Tenbury and Harding collections and the library of John Locke, he spent a period as Head of Catalogue Support Services before returning to head up the Music Section on the retirement of Peter Ward Jones in 2009. He has a particular interest in English music and has written on various subjects, including the composer Ernest Farrar, the development of the Bodleian’s legal deposit music collections and the provincial book trade.

The manuscript is currently on display until 17 August 2025 as part of Bach: A Composer’s Obsession, a free display in Blackwell Hall, Weston Library. The manuscript is shown alongside a selection of items which illustrate the importance of Bach in the life and work of a later composer, Felix Mendelssohn.

Bach 1725, with a manuscript viewing and pre-concert talk, will take place at the Sheldonian Theatre on Wednesday 7 May.

Ahead of Bach 1725, Professor Martyn Harry spoke with renowned composer Judith Weir, whose new composition will premiere at the celebration concert on Wednesday 7 May. Commissioned by the Bodleian Libraries, Weir’s piece offers a contemporary reflection on Bach’s Ascension Day Cantata (BWV 128). Known for her innovative approach to storytelling through music, Weir shares the inspiration behind this new work, her experience of engaging with Bach’s music, and what she hopes audiences will experience during this special celebration.

Martyn Harry: Can you please tell us about your new work Upwards and how it relates to the Bach manuscript celebrated in tonight’s concert?

Judith Weir: I approached Upwards as an overture to the Bach cantata we are talking about – Auf Christi Himmelfahrt allein. It uses the same instruments as the whole cantata, including two horns and trumpet. Although I think it’s the case that in Bach’s day the trumpet player would have been one of the horn players, I took the opportunity to have the whole lot of them. I wanted it to be very closely related to the first movement of the cantata, because after all my piece will be immediately preceding that first movement. In other words, I was ignoring the rest of the cantata and just looking at that huge opening movement, which is a chorale-prelude, with a chorale sung by the trebles, very slowly over the top of the music.

I looked at the Bach both in the manuscript and the printed version, and started off by looking at actual figures that Bach uses to accompany his chorale. From there, I started to add my own notes and rhythmic figures. The thing that is so obvious in the whole cantata (about Ascension Day) is that the chorale melody in this movement is very flat in terms of contour whereas everybody else is playing leaping upwards figures all the time. So that really became my concept for the piece: the individual things that people play should always tend to be upwards scales or melodies in some way. And generally speaking, the music moves upwards through the piece and ends as an almost pictorial attempt at going up into the sky.

MH: This commission presents an exciting challenge in writing for the instruments and players of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment. What is your approach for composing for early music instruments?

JW: I think particularly with instruments that we don’t really have now, like the oboe d’amore and the oboe da caccia, just to try and find out about them. To imagine as closely as possible the experience of the performers as they play these instruments. Speaking about those woodwind instruments, they don’t have so many helpful keys as modern instruments, so you have to think about the shape of your melodies: will this work for them? And of course, looking at these incredibly high brass parts in both the horns and the trumpets that we’re not used to in modern orchestral music. It would be a big ask to have, for instance, the horns playing quite so high all the time, but it certainly seems to work in the Bach.

So, I think my approach there is just to try and understand how those instruments are played and how can they do that. And of course it is terribly important to try and work out what the instruments can’t do, so for instance, these natural horns, they don’t have any extra valves, so you have to imagine them just playing a metal tube that can just play the harmonic series, plus maybe a little bit where the embouchure, the lip position, might help you to play something a little flatter or something like that. But on the whole, I try not to think of it as a restriction, it’s a chance to hear very different tones in the music I am going to write.

MH: When I first met you, you played the oboe. Have you found yourself re-engaging with your own playing experience of the oboe, given that there are three different types of oboe available in this piece?

JW: Well, I was lucky as a student that someone lent me a baroque oboe (it might have been a reconstruction). I didn’t make much of it! It was terrifically hard to think about how to create a reed and get it to do anything. So, I massively admire all the people in the last fifty years who have done that to such a high standard.

My memories of playing Bach as an oboe player are about the breath, the enormous solos that you play, particularly in the solo arias – we’ve got one actually in this piece – and just how strong and how careful you have to be about finding places to breathe. I do marvel at the fact that Bach’s work is just full of these. They are gorgeous tunes; they’re probably the best ever. But oboe music, it’s extremely difficult to play. And I guess, seeing these historical instruments, at least the physical strain isn’t so great, but I would think the finger problems must be pretty considerable!

Professor Martyn Harry is Professor of Composition at the Music Faculty, University of Oxford as well as a Fellow and Tutor at St Anne’s College and Lecturer at St Hilda’s College.

If you’d like to be there for the premiere of Judith Weir’s new work Upwards as part of a Bach celebratory concert, tickets are still available for Bach 1725 taking place on Wednesday 7 May. Presented by the Cultural Programme at Oxford University and the Bodleian Libraries.

On Wednesday 7th May 2025, the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment will mark the 300th anniversary of Johann Sebastian Bach’s 1725 Ascension Day cantata Auf Christi Himmelfahrt allein (BWV 128) with a performance at Oxford’s Sheldonian Theatre produced by the Oxford Cultural Programme. The event will feature a world premiere from Judith Weir, one of the UK’s most celebrated contemporary composers, commissioned by the Bodleian Libraries. Weir’s composition was created in direct response to the autograph manuscript of Auf Christi Himmelfahrt allein, acquired by the Bodleian Libraries via the government’s Acceptance in Lieu scheme in 2024.

The concert is a rare opportunity to experience Bach’s festive and colourful composition for orchestra, chorus, and soloists, originally written for Ascension Day in May 1725. John Butt, a world-leading Bach scholar and performer, will direct the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment alongside the Choir of New College, Oxford, under the guidance of its director, Robert Quinney. Adding to the evening’s significance, the programme will feature new works from student composers Daniel Reynolds and Nick Samuel from the Faculty of Music at Oxford University, responding to Bach’s enduring legacy.

The Kohn manuscript of BWV 128, formerly owned by the Leipzig-born collector Sir Ralph Kohn, is one of only four Bach manuscripts in the UK. It will appear on public display at the Weston Library ahead of the concert, offering audiences a rare chance to connect Bach’s creative process to a tangible object. Despite his prolific production, very few of Bach’s works were published in his lifetime, and without the miraculous survival of his autograph manuscripts in institutional collections, most of his masterpieces would be lost. The document has been exceptionally well cared for and the erosion of paper is mostly limited to the edges, making this one of the best-preserved autographs of Johann Sebastian Bach.

Judith Weir’s New Composition

As part of this celebration, the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment will premiere a new work by Judith Weir, former Master of the King’s Music, commissioned by the Bodleian Libraries. Renowned for her innovative approach to storytelling through music, Weir’s composition will offer a contemporary reflection on themes from Bach’s cantata. The manuscript of this new work will pass into the Bodleian Libraries’ collections, meaning that both this new work and Bach’s original piece will be preserved for posterity.

Judith Weir said: “Following so closely in J S Bach’s footsteps – and indeed his pen strokes and ink blots – has been a unique and joyous experience. Mirroring Bach’s original score note-for-note, it’s impossible not to be influenced by the extraordinary energy and uplift of his Ascension music. The opportunity to present my new score to the Bodleian Libraries reflects my own feeling of inheritance as a lifelong listener to Bach’s music.”

Auf Christi Himmelfahrt allein

Auf Christi Himmelfahrt allein was composed for the feast of the Ascension, 10 May 1725, celebrating Christ’s triumphant rise to Heaven forty days after the Resurrection, but it did not appear in print until 1878, 150 years after it was composed.

The short, festive cantata, which lasts less than 20 minutes in performance, is scored for two horns, three different types of oboe, trumpet, strings and continuo, with four-part chorus, and alto, tenor and bass soloists. Its five movements comprise a celebratory opening chorus, a short recitative and aria for bass voice, a duet for alto and tenor, ending with a simple chorale. The music for this cantata was all new, which is relatively unusual for Bach who frequently recycled and adapted movements from his other compositions.

The text for Auf Christi Himmelfahrt allein was written by Marianne von Ziegler—the only known female librettist Bach worked with. A pioneering figure in 18th-century Leipzig, von Ziegler was an accomplished poet and intellectual who defied societal norms, gaining recognition in her lifetime without adopting a male pseudonym. Her collaborations with Bach in 1725 produced a sequence of extraordinary cantatas, yet the full extent of their working relationship remains a mystery.

Bach 1725 is taking place on Wednesday 7 May at the Sheldonian Theatre – tickets are available now. You can also look at the Kohn manuscript online on Digital Bodleian.

In 1725, Johann Sebastian Bach partnered with poet Christiana Mariana von Ziegler for a series of nine cantatas. Bach’s compositions combine choral and instrumental music, and were crafted to enhance the religious services of the Lutheran church throughout the liturgical year.

Christiana Mariana von Ziegler assisted Bach as his librettist – she provided the words to be used alongside his music. This International Women’s Day, we’re uncovering a lesser-known chapter in the history of Johann Sebastian Bach’s cantata for Ascension Day: ‘Auf Christi Himmelfahrt allein’ (BWV 128), Kohn manuscript, which was acquired by the Bodleian Library in 2024.

Ahead of the Bach 1725 celebration this spring, marking 300 years since the first performance of Bach’s cantata for Ascension Day, join Professor Henrike Lähnemann as she explores the life, legacy, and contributions of one of Bach’s key collaborators.

In 1725, Johann Sebastian Bach faced a dilemma: he had run out of texts for the weekly offering of cantatas to be performed in the main churches of Leipzig, and there were still nine Sundays to fill for the prime festive season of the year, from Jubilate Sunday (the third after Easter) via Ascension and Whitsun to Trinity Sunday, the feast that still gives its name to Oxford’s third term. To his rescue came a young woman, Christiana Mariana von Ziegler (1695–1760). She provided, with a remarkably quick turn-around, the libretti for the Sundays that Bach was still missing in order to complete his second choral cantata cycle, among them the Ascension Day cantata ‘Auf Christi Himmelfahrt allein’ which became BWV 128, the autograph manuscript of which is now held in the Bodleian Library. Who was this woman who could so readily produce singable verse which would be very publicly performed in the city space?

Christiana Mariana von Ziegler held an unusual position in Leipzig at the time. Having already been widowed twice and having lost the children from both marriages, she returned to her mother’s house in Leipzig in 1722 and turned it into a literary and musical salon – one of the few artistic meeting places Leipzig had to offer, and Bach, who took the position as Thomaskantor (musical director) in 1723, was a regular visitor, as well as Johann Christoph Gottsched (1700–1766), the heavy-weight critic of his age who arrived in Leipzig in 1724.

The cantata collaboration of Ziegler and Bach is a product of this artistic networking in the Leipzig circle. Particularly fascinating is that the cantata text shows an ongoing debate about the nature of religious poetry. Ziegler’s secular texts tended to display enlightenment characteristics: critical, satirical, formally balanced and full of learned references. Bach, on the other side, usually chose libretto writers close to the Pietist movement of his time and kept his distance to the rationalist style of poetry of the Gottsched circle.

Ziegler’s cantata texts show that she tried to accommodate Bach’s wishes and completely dispensed with the unusual comparisons and playful allegories that she otherwise loved. For the cantatas, she, like Bach’s other lyricists, drew from the sermon literature of the time and incorporated traditional exegetical material. The argumentation structure of the cantata BWV 128 depends on the popular sermon cycle Evangelischer Hertzens-Spiegel (‘Gospel-based Mirror for the Heart’, 1679) by the theologian and poet Heinrich Müller (1631–1675), which was continuously reprinted until in the 18th and 19th centuries and formed part of both von Ziegler’s and Bach’s library. Still, Bach intervened more heavily with her libretti than with any other text he set, emphasizing biblical quotations and adding a warning against trying to intellectually grasp God’s secret. Reading his autograph manuscript against her published version of the cantata text opens up a glimpse into the intellectual debates about religion and human understanding which must have been going on in the meetings at Ziegler’s house.

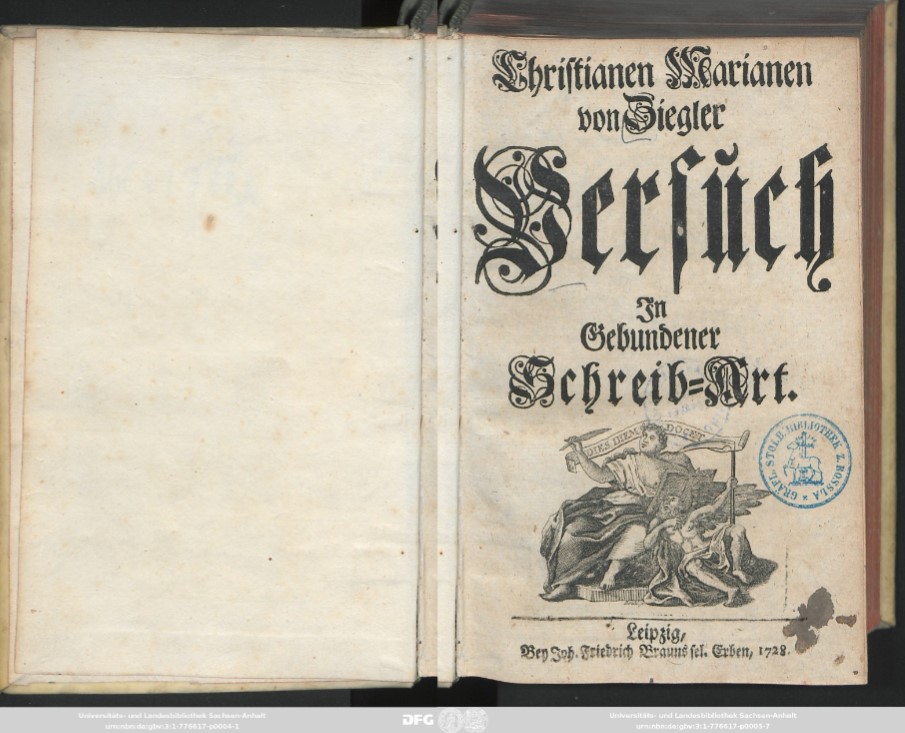

What became of Ziegler after this collaboration with Bach? She published the cantata texts four years later, joined with other devotional poems to form a cycle ( ‘Andächtige Gedichte’) in the second volume of her ‘Versuch in gebundener Schreib-Art’ (‘attempt in the art of verse writing’), which earned her as first and only woman a membership of Gottsched’s ‘Deutsche Gesellschaft’. This ‘German Literary Society’ was part of the early enlightenment movement and publicly active to promote German literature and language. This in turn made Ziegler eligible for the society’s annual poetry prize which she won twice, in 1732 and 1734. On 17 October 1733, she was made Poet Laureate by the University of Wittenberg – the Baroque equivalent of the Noble Prize for Literature. Her early collaboration with Bach was clearly an indication of great things to come!

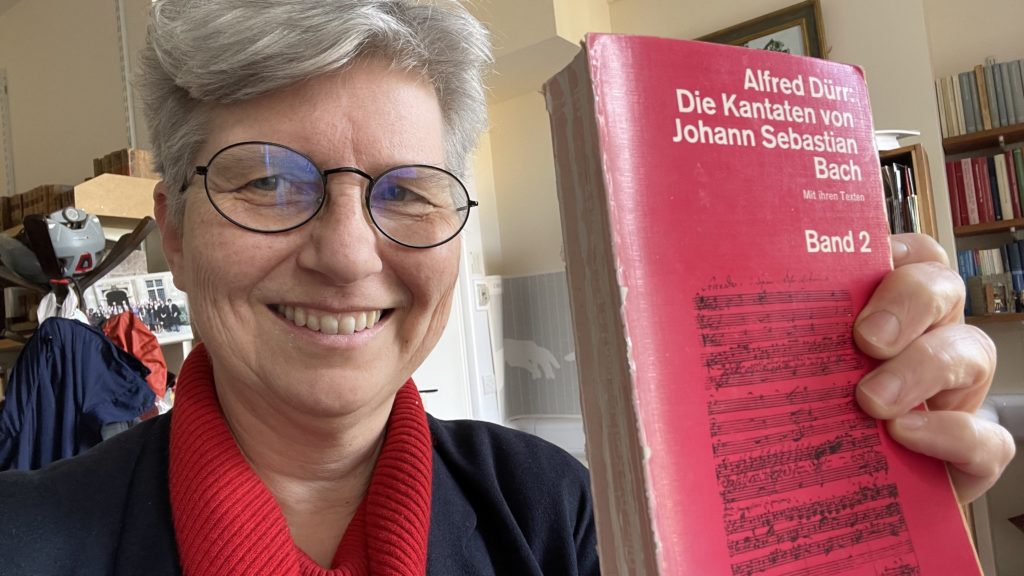

When I grew up in the 70s and 80s, the two pink paperback volumes of Alfred Dürr’s edition of Bach cantata texts had their permanent place next to the radio on the bookshelf in the vicarage of my grandparents, to be perused on Sunday mornings to follow the text of the weekly broadcast of the Bach cantata for the day. It was a cultural practice in many households around Germany and the common sentiment was: ‘wonderful music, pity about the text’ – the emotional piety focussing on the wounds of Christ and Baroque exuberance of images sat uneasily with post-war sober and minimalist aesthetics.

When Elke Axmacher, a young lecturer at the Kirchliche Hochschule Berlin, a theological college then part of the Freie Universität, offered a seminar in the summer term of 1991 focussing on the theology, imagery and rhetoric of the cantata texts, I was intrigued. I borrowed my grandparents’ by now faded pink volumes and set out to read my way through it from the perspective as literature. I was most struck by the aesthetic sense and well-crafted poetics of the Ascension Cantata by Christiane Mariane von Ziegler. And I was also fascinated when I realised that it was the cantata text with which Bach had probably most heavily intervened and wrote my essay for the course on this cantata. Imagine my delight when 33 years after this seminar I learned that the Bodleian Library had acquired the autograph manuscript of this particular cantata – and that this coincides with the start of a major new edition project at the University of Karlsruhe which will highlight the feminist and enlightenment aspects of Ziegler’s work.

I am looking forward to a workshop with musicologists, theologians, and philologists in May from Germany, Switzerland and Britain to discuss Ziegler’s texts after listening to Bach’s setting of her cantata text in the glorious surroundings of the Sheldonian Theatre!

Tickets for the Bach 1725 celebration on Wednesday 7 May, including a manuscript viewing and evening performance by the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment and the Choir of New College Oxford, are available now.