Female Enlightenment: Christiana Mariana von Ziegler as librettist for Bach

In 1725, Johann Sebastian Bach partnered with poet Christiana Mariana von Ziegler for a series of nine cantatas. Bach’s compositions combine choral and instrumental music, and were crafted to enhance the religious services of the Lutheran church throughout the liturgical year.

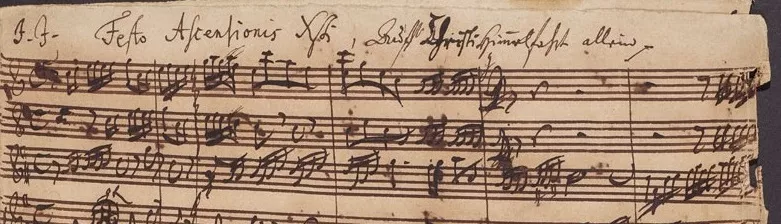

Christiana Mariana von Ziegler assisted Bach as his librettist – she provided the words to be used alongside his music. This International Women’s Day, we’re uncovering a lesser-known chapter in the history of Johann Sebastian Bach’s cantata for Ascension Day: ‘Auf Christi Himmelfahrt allein’ (BWV 128), Kohn manuscript, which was acquired by the Bodleian Library in 2024.

Ahead of the Bach 1725 celebration this spring, marking 300 years since the first performance of Bach’s cantata for Ascension Day, join Professor Henrike Lähnemann as she explores the life, legacy, and contributions of one of Bach’s key collaborators.

In 1725, Johann Sebastian Bach faced a dilemma: he had run out of texts for the weekly offering of cantatas to be performed in the main churches of Leipzig, and there were still nine Sundays to fill for the prime festive season of the year, from Jubilate Sunday (the third after Easter) via Ascension and Whitsun to Trinity Sunday, the feast that still gives its name to Oxford’s third term. To his rescue came a young woman, Christiana Mariana von Ziegler (1695–1760). She provided, with a remarkably quick turn-around, the libretti for the Sundays that Bach was still missing in order to complete his second choral cantata cycle, among them the Ascension Day cantata ‘Auf Christi Himmelfahrt allein’ which became BWV 128, the autograph manuscript of which is now held in the Bodleian Library. Who was this woman who could so readily produce singable verse which would be very publicly performed in the city space?

Christiana Mariana von Ziegler held an unusual position in Leipzig at the time. Having already been widowed twice and having lost the children from both marriages, she returned to her mother’s house in Leipzig in 1722 and turned it into a literary and musical salon – one of the few artistic meeting places Leipzig had to offer, and Bach, who took the position as Thomaskantor (musical director) in 1723, was a regular visitor, as well as Johann Christoph Gottsched (1700–1766), the heavy-weight critic of his age who arrived in Leipzig in 1724.

The cantata collaboration of Ziegler and Bach is a product of this artistic networking in the Leipzig circle. Particularly fascinating is that the cantata text shows an ongoing debate about the nature of religious poetry. Ziegler’s secular texts tended to display enlightenment characteristics: critical, satirical, formally balanced and full of learned references. Bach, on the other side, usually chose libretto writers close to the Pietist movement of his time and kept his distance to the rationalist style of poetry of the Gottsched circle.

Ziegler’s cantata texts show that she tried to accommodate Bach’s wishes and completely dispensed with the unusual comparisons and playful allegories that she otherwise loved. For the cantatas, she, like Bach’s other lyricists, drew from the sermon literature of the time and incorporated traditional exegetical material. The argumentation structure of the cantata BWV 128 depends on the popular sermon cycle Evangelischer Hertzens-Spiegel (‘Gospel-based Mirror for the Heart’, 1679) by the theologian and poet Heinrich Müller (1631–1675), which was continuously reprinted until in the 18th and 19th centuries and formed part of both von Ziegler’s and Bach’s library. Still, Bach intervened more heavily with her libretti than with any other text he set, emphasizing biblical quotations and adding a warning against trying to intellectually grasp God’s secret. Reading his autograph manuscript against her published version of the cantata text opens up a glimpse into the intellectual debates about religion and human understanding which must have been going on in the meetings at Ziegler’s house.

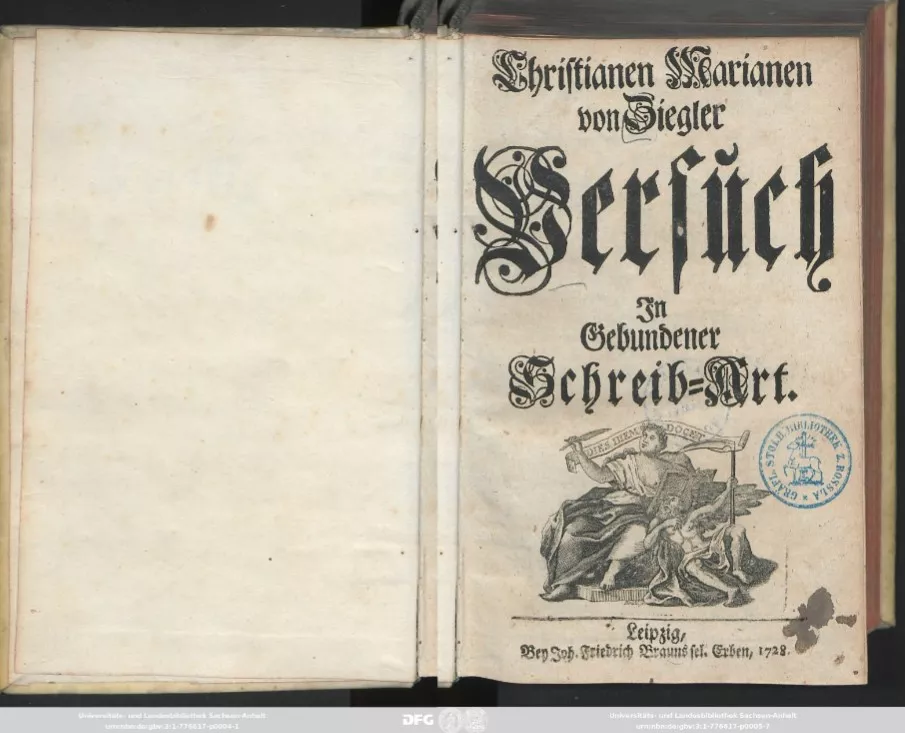

What became of Ziegler after this collaboration with Bach? She published the cantata texts four years later, joined with other devotional poems to form a cycle ( ‘Andächtige Gedichte’) in the second volume of her ‘Versuch in gebundener Schreib-Art’ (‘attempt in the art of verse writing’), which earned her as first and only woman a membership of Gottsched’s ‘Deutsche Gesellschaft’. This ‘German Literary Society’ was part of the early enlightenment movement and publicly active to promote German literature and language. This in turn made Ziegler eligible for the society’s annual poetry prize which she won twice, in 1732 and 1734. On 17 October 1733, she was made Poet Laureate by the University of Wittenberg – the Baroque equivalent of the Noble Prize for Literature. Her early collaboration with Bach was clearly an indication of great things to come!

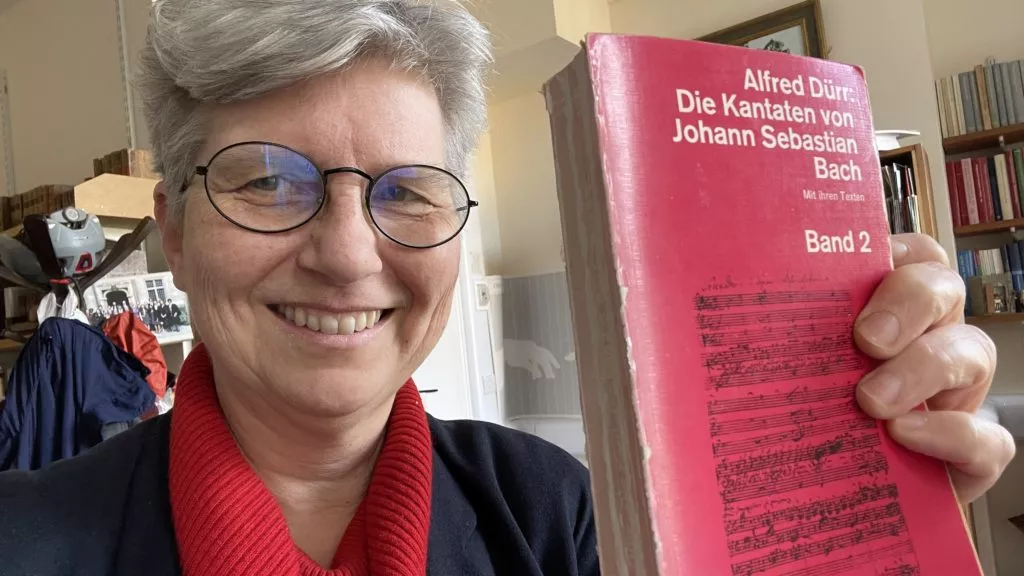

When I grew up in the 70s and 80s, the two pink paperback volumes of Alfred Dürr’s edition of Bach cantata texts had their permanent place next to the radio on the bookshelf in the vicarage of my grandparents, to be perused on Sunday mornings to follow the text of the weekly broadcast of the Bach cantata for the day. It was a cultural practice in many households around Germany and the common sentiment was: ‘wonderful music, pity about the text’ – the emotional piety focussing on the wounds of Christ and Baroque exuberance of images sat uneasily with post-war sober and minimalist aesthetics.

When Elke Axmacher, a young lecturer at the Kirchliche Hochschule Berlin, a theological college then part of the Freie Universität, offered a seminar in the summer term of 1991 focussing on the theology, imagery and rhetoric of the cantata texts, I was intrigued. I borrowed my grandparents’ by now faded pink volumes and set out to read my way through it from the perspective as literature. I was most struck by the aesthetic sense and well-crafted poetics of the Ascension Cantata by Christiane Mariane von Ziegler. And I was also fascinated when I realised that it was the cantata text with which Bach had probably most heavily intervened and wrote my essay for the course on this cantata. Imagine my delight when 33 years after this seminar I learned that the Bodleian Library had acquired the autograph manuscript of this particular cantata – and that this coincides with the start of a major new edition project at the University of Karlsruhe which will highlight the feminist and enlightenment aspects of Ziegler’s work.

I am looking forward to a workshop with musicologists, theologians, and philologists in May from Germany, Switzerland and Britain to discuss Ziegler’s texts after listening to Bach’s setting of her cantata text in the glorious surroundings of the Sheldonian Theatre!

Tickets for the Bach 1725 celebration on Wednesday 7 May, including a manuscript viewing and evening performance by the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment and the Choir of New College Oxford, are available now.