Let’s Build a Town! and the Importance of Play

Ahead of a special evening performance this March, in which Oxford schoolchildren will bring their visions of an ideal town to life through original music and theatre, Giles Masters (Fellow, Magdalen College) delves into the inspiration behind the project and highlights the essential role of play in learning and development. This behind-the-scenes look at the collaboration between researchers and primary school students explores the influence of music and theatre experiment, Wir Bauen Eine Stadt (1930), and its relevance for children today.

Red light! Green light! Motorway! Four eight-year-olds are telling me how you play a game called ‘Cars’. (Initially, there’s some debate about whether the name is actually ‘Beans’, but on reflection we decide this is unlikely.) Folded into a tiny red plastic chair – an adult guest in their primary school classroom – I learn that the game, which they play in PE, involves responding to verbal prompts from a leader or teacher. ‘Green light!’ means go; ‘red light!’ means stop. ‘Tow truck!’ means find a partner and hold their hand. ‘Mini car!’ means shuffle along with your knees bent in a kind of squat. (Children find this easier than grown-ups.) And if you hear ‘motorway!’, run as fast as you can. The game ends with ‘park!’: everyone sits down. For the children, recalling and demonstrating each of these actions quickly becomes its own kind of game: a game about the power of memory, about the satisfaction of communicating something important to an ignorant adult (who doesn’t know ‘Cars’?), and about the almost unbearable question of how long they’ll have to wait before they play the real thing again.

This isn’t what I usually get up to in my job. As a music historian, I’m most often to be found in an archive or library somewhere or teaching young adults and marking their essays. In the project that brought me into this primary school classroom, those familiar ways of thinking about knowledge and learning in a university humanities department remain essential. But the aim is to put them to more creative, experimental ends, involving a much bigger, more varied team of collaborators and a lot more running around pretending to be cars.

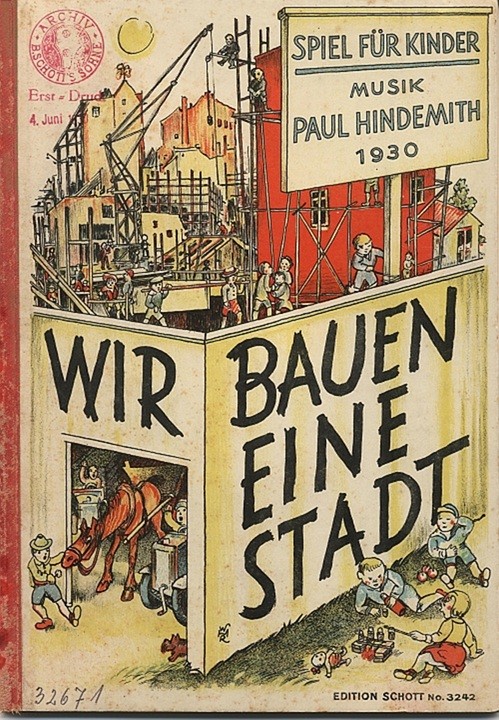

On behalf of Music at Oxford, with kind permission of Schott Music, Mainz, Germany.

The project, Let’s Build a Town!, began in summer 2023, when I took the initial germ of an idea to Felicity Newby-Smith, who runs the Learning and Participation programme for Music at Oxford, a local arts organisation. The starting point was my research into Wir bauen eine Stadt (Let’s Build a Town) by the German composer Paul Hindemith. In summer 1931, this short, recently composed experiment in music theatre was performed by British schoolchildren in Oxford’s Holywell Music Room. This fascinating, basically unknown historical event sparked us to think about how the piece might be revived and reimagined in Oxford today.

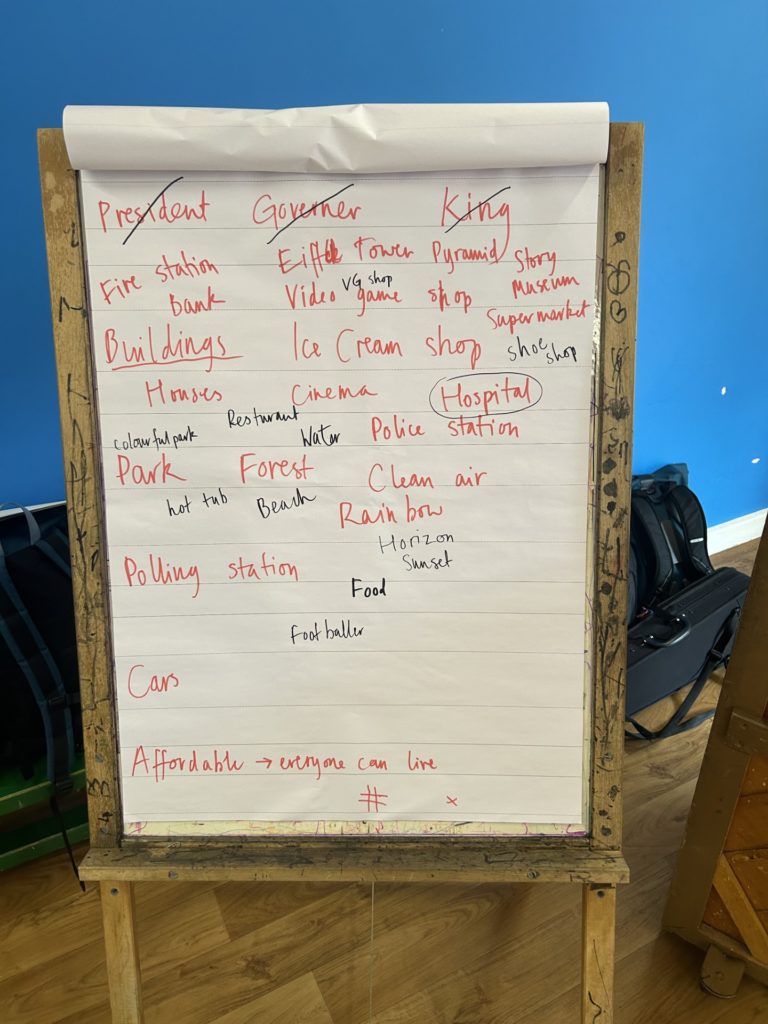

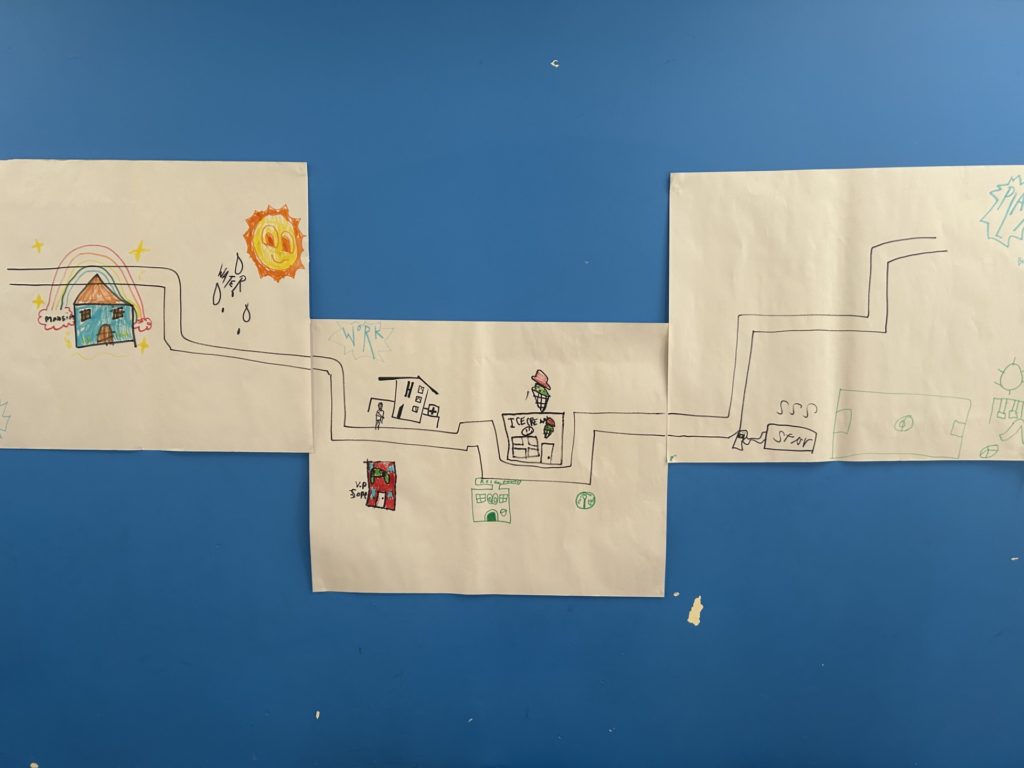

We found two aspects of Wir bauen eine Stadt especially inspiring. First, the work invites children to imagine a city where there are no adults and they are in charge. This classic scenario (explored most famously, and disturbingly, in English-language literature in William Golding’s 1954 novel Lord of the Flies) is presented optimistically here as a kind of urban utopia. During the piece, the children think about the different kinds of infrastructure that make up a city, such as transport. They imagine what kinds of roles they might take up in this new society. (We’ll still need a dentist.) And they teach us about the importance of working together to get things done. Today, in Oxford and across the country, debates around urban planning, citizenship, and belonging are urgent and often highly divisive. In this context, Wir bauen eine Stadt offers rich opportunities for young people to develop and express their views on local history, geography, and politics, and to foreground their voices, so easily ignored, in renewed and less polarised public discussions on these themes. How do children in twenty-first-century Oxford think about their city, we wondered, and if they were in charge, what kind of place and community would they want to live in? After all, they are the ones who will have to live with the decisions we make today.

Second, Wir bauen eine Stadt is suffused with the belief, widespread among progressive-minded artists and teachers of Hindemith’s generation, that games and play are essential to fostering children’s learning, social development, and enjoyment of the arts. That belief makes a refreshing contrast with the narrow views of education that have squeezed the space for creativity and performance in UK school curricula over the past decade or so. Hindemith’s main collaborator, a writer called Robert Seitz, came up with material for Wir bauen eine Stadt by observing playground games that early twentieth-century German children played of their own accord and translating these into corresponding dramatic situations (so we get, for example, a night-time caper involving cops and robbers). Felicity and I wanted to explore what might happen if we took this ethos one step further: that is, if instead of simply harvesting ideas from children’s games (and then retreating to the risk-averse territory of getting children to learn words and music written by adults), we made play a more integral part of the creative process and performance. With this aim in mind, we devised a project in which young people would be empowered to build and perform a new, more genuinely playful, version of Hindemith’s ‘town’, in which scenes from the original work would be interwoven with new co-created music and theatre exploring the same themes from the twenty-first-century perspectives of the children taking part.

In late 2023, the project was awarded incubation funding from the Cultural Programme. This support enabled us to organise two developmental workshop days in July and September 2024 at St Francis CofE Primary School in east Oxford. (St Francis, our main partner school, has an existing link with the Outreach and Access Team at Magdalen College, where I am a Fellow by Examination.)

We were lucky to have a brilliant team of artists and workshop leaders: Emma-Jane Greig (movement), Oliver Grant (theatre), Tabitha Grove (design), Tim Keasley (music lead), Rose Martin (music/singing coach), Anna Pool (director), Lauren Spiceley (music/instrumentalist), and Natalie Wong (movement). The team was completed by Dr Lucy Hunt, who led evaluation of the incubation period, with support from Erin Townsend (a third-year undergraduate music student).

During the workshop days, we split our time between developing ideas as a project team and working directly with young people in Years 4 and 5 (aged 8–10). We focused especially on collecting different kinds of games, drawing on the collective knowledge of the children and grown-ups, and thinking about how they might be used or adapted for the project. We also worked with some of the children to try out new games we had just invented and to draw a big collective map of their ideal town. In July we led a whole-school singing assembly, and in September we taught both classes we’re working with one of the songs by Hindemith. At the end of the assembly, the St Francis community gave us a very special surprise, singing ‘The Trees of the Fields Will Clap Their Hands’, one of their favourite songs, just for us.

Working with games and play raised a host of fascinating questions, philosophical and practical. What do these terms actually mean? Can we draw a clear boundary between them? And how might we categorise the myriad activities they refer to? One helpful parameter was structure: how much what an individual does is governed by rules. At one end of this scale, we might put organised sports and certain board games. At the other, there are freer activities that rely more on the imagination (such as ‘Playing House’). Many games fall between these extremes. Other parameters and categories that seemed important included the number of players, the presence or absence of a leader figure (like in ‘Cars’), and the amount of energy and physical exertion required (an important consideration when planning workshops with primary school children!). We also tracked the continuities and changes between the games the young people talked about enjoying, the ones we remembered from our own childhoods, and the ones that feature in Hindemith’s piece. We learnt, for instance, that these children still play ‘Grandmother’s Footsteps’ – but, disconcertingly, they call it ‘Squid Game’. In the playground, word-of-mouth knowledge and popular culture are constantly colliding in new ways.

What has been most rewarding, after many months of planning, has been to start collaborating with the children in meaningful and even inspiring ways. As the Year 4 class teacher wrote to us after the September workshop, ‘The children’s engagement has been incredibly high due to the wealth of skills and enthusiasm of the adults involved as well as the carefully thought-out activities. The sessions have been accessible for all children, and it has been great to see positive engagement from those who may not usually see performing or music as “their thing”. Children were left with an excited buzz about the project.’ A town worth living in can’t be built in a day. But during this first phase of the project, we’ve worked hard to lay down the best foundations we can. We look forward to sharing more updates with you, and we hope you can join us for the final performance in March!

‘Let’s Build a Town’ is produced by Music at Oxford in collaboration with The University of Oxford’s Cultural Programme, and with the support of the Faculty of Music, Magdalen College, RETUNE Festival and the Marchus Trust.

Join Giles Masters and members of the artistic team on 5th March for a unique opportunity to explore the research and creative work behind the project at a pre-concert discussion and workshop. Tickets are free and available now from Florence Park Talks.

Enjoy original music and theatre created as part of the project on 14th March – a new town will be imagined and built before your eyes and ears! Find out more about the ‘Let’s Build a Town‘ evening concert. – tickets are available now.